By Ayelet Baram-Tsabari, Orli Wolfson, Elad Segev

Too basic to mention, a truism too dull to repeat, jargon is still one of the greatest hurdles to effective science communication. Despite all the emphasis on dialogue and participatory actions, it's almost impossible for readers to understand a text if the vocabulary is more akin to a foreign language. With COVID-19 dictating our movements and social interactions, we are dependent today more than ever on the engagement of individuals from all walks and talks of life with public health guidelines and policy. These are spelled out in the languages of values and biology, ethics, and medicine.

Jargon concerns us both as science communication researchers who aim for interdisciplinary collaboration and visibility, and as science communication practitioners who recognize the need to communicate scientific concepts in vivid and familiar ways. To do so, we need to support scientists to learn how to talk about science in new ways. Naturally, science communication researchers and practitioners also need to talk to each other to identify and co-create evidence-based work to direct our practice. It makes truly little sense to support informed science-based decision making while ignoring that directive when it comes to our own practice.

It takes two to tango. The small number of practitioners drawing on science communication scholarship as a resource is not a source of pride for our field. A 2007 UK survey found that only 42% of the attendees at a science communication conference read PUS and 36% read Science Communication at least occasionally, whereas 55% never read either journal. In Germany, a representative survey showed that hardly any practitioners knew, let alone used, scholarly journals. This is most likely the case in many other non-English speaking countries. I can attest for Israel.

This does not imply that new approaches and findings are not being popularized or finding their way into practitioners' work. Nor does it suggest that jargon is the main or sole hurdle standing in the way of a fruitful intra-disciplinary dialogue. But jargon does matter.

In our latest article - Jargon use in Public Understanding of Science papers over three decades- we took up the challenge put forward by Public Understanding of Science (PUS) editor Hans Peter Peters and direct our attention to our own discourse in Public Understanding of Science. PUS is an interdisciplinary journal, which aims to serve diverse audiences. Its mission, according to the journal, is to cater to the community of scholars, scientists of all disciplines, research managers, and science communication practitioners. We decided to examine whether and how jargon use and readability have changed in the decades since its founding.

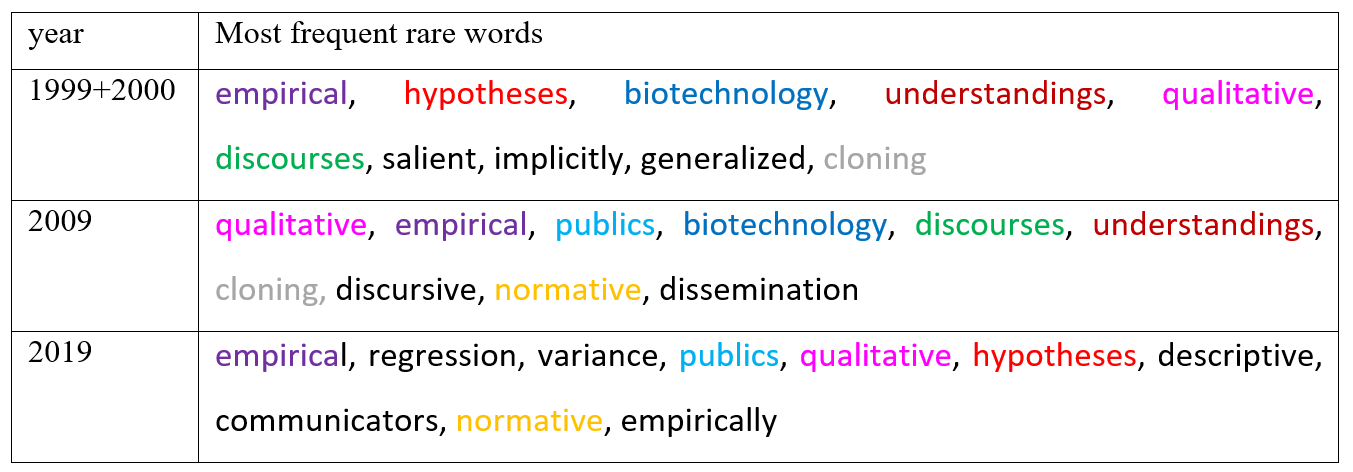

The papers that were published in 1999/2000 (47), 2009 (49) and 2019 (65) were tested for their readability (using the Flesch Reading formulas) and their use of jargon using the De-Jargonizer. We found that readability has decreased and the use of jargon has increased in the period between 1999/2000 and the last twenty years.

Specifically, authors used fewer rare words in 1999/2000 than today. Rare words are not necessarily a bad thing, since the shift in vocabulary might reflect the professionalization of the field. To test this, we omitted all words appearing on the general academic vocabulary list. We found that the percentage of general academic words was higher in 1999/2000 than more recently. This may indicate that more words that are specific to the science communication discipline have been added to discourse. However, it may also indicate that earlier papers used more general academic vocabulary that the readers of PUS probably understood (Table 1).

The popularity of methodological words, for example, has changed. In 1999/2000 the rare word 'correlations' appeared rather frequently, but since then ‘regression’, ‘variance’, and ‘predictors’ as rare-but-frequent methodological words have replaced it. Methodological words are a good example because they are classic jargon: researchers get attached to them. But one's old friends, such as 'discursive' or ‘regression', may seem strange to other professionals. As scholars, we cannot totally avoid them, but we should try to avoid the avoidable.

Do science communication scholars develop their own professional vocabulary? We explored this question by comparing the most frequent words that were identified as “rare” in papers published in 2019 that were (a) shared by the community (appeared in more than one article) versus those that were (b) exclusive to only one paper (Figure 1). The results showed that most of the frequently used rare words were not exclusive to science communication. “Popularization”, and naturally, “PUS” might be considered “our” jargon.

|

| Fig. 1A. Frequent and shared by the community: Examples of words appearing in more than one article, listed by the number of different articles (the number next to the term). |

|

| Fig. 1B. Frequent and exclusive: Examples of words that appeared in only one article in 2019. |

Automatic tools for identifying potential jargon in a text may be valuable for those who write about science, because they point out words that have become second nature to some, but could be incomprehensible to readers. A recent paper “Quantifying scientific jargon” provides a publicly available R script that measures the level of jargon in text. They also calculated standard jargon values for different text genres, so the user can evaluate the level of jargon with respect to a specific audience.

Useful one, keep sharing..

ReplyDelete